The subject of motivation is a complex one—in short, it’s an intangible variable that can ebb and flow widely in short periods of time. Athletes with seemingly unparalleled drive lose it. Loafers show up to practice one day with a fire lit inside them. From week to week, teams, athletes, and coaches fluctuate in their intensity and level of dedication.

Norman Triplett is generally credited with the first formal experiment in sport motivation psychology. A psychologist at Indiana University, Triplett was a bicycle enthusiast who had noticed that racers seem to ride faster in pairs than alone. In 1889, he tested his hypothesis by asking children to reel in fishing line in a number of competitive conditions. As predicted, the children reeled in more line when they performed next to another child. The same held true when Triplett examined racing times—cyclists rode faster when paced or pitted against others than when they rode by themselves.

Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud argued that motivation was a product of the subconscious instincts of sex

and aggression. Our behavior, he said, is largely shaped by our instincts.

Behaviorist B.F. Skinner was on the other end of the nature–nurture continuum. He didn’t believe in

the subconscious. To explain motivation, Skinner put forth stimulus–response psychology, claiming that all behavior is controlled by external reinforcements. We are essentially a black box, Skinner said; what goes in determines what comes out.

Although their beliefs were radically different, these psychologists agreed on one thing: Motivation is not up to the individual. They professed humans to be, essentially, products of genetics or the environment. The argument at the time laid groundwork for the nature-versus-nurture debate that still continues today: Is our behavior dictated by our biological makeup or is it a product of what our experiences have taught us? The answer is both.

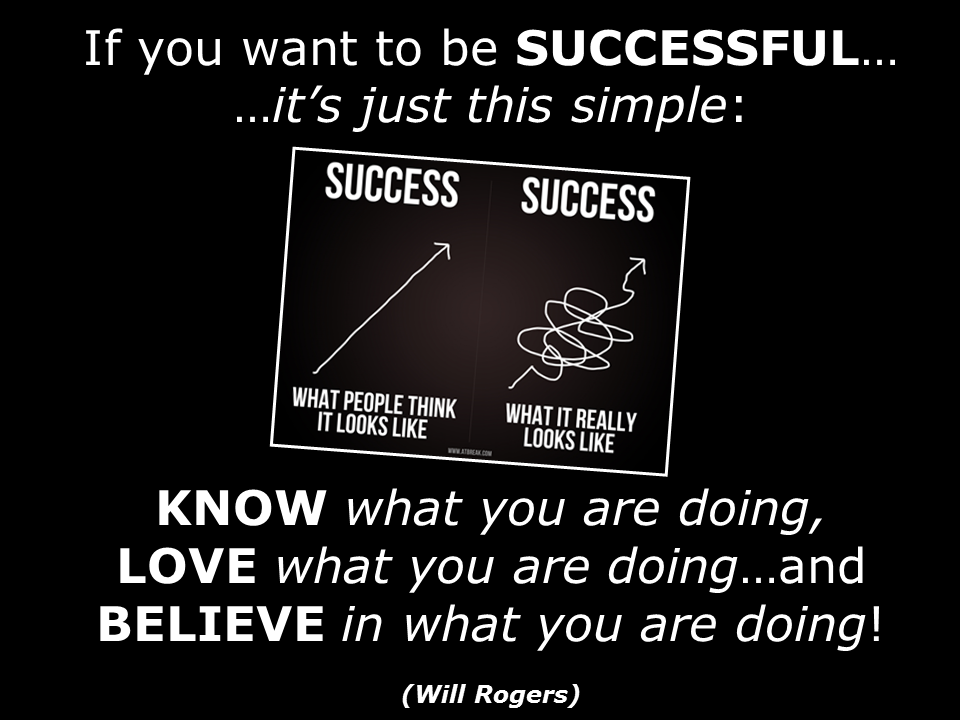

The most robust motivation—the sort that can push through four years of grueling training for the Olympic Games, or dealing with a coach who doesn’t believe in you—is rooted in the heart and the soul. Motivation strategies should foster autonomy, competence, and connectedness. Examples include:

Push the edge - Find a weakness or hole in your game and get excited about where your game will be after you change it. Similarly, be creative. Think up something no one in your sport has dared or perfected. Experience success - When learning new skills and strategies, go step-by-step. Start with an easy piece, master it, and then move on to the next-easiest piece. Or begin by modifying the skill to something you can do well. Let yourself experience success. Keep track of your PRs and how many times you can break them.

Change your thinking - The old adage about learning from your mistakes is well and good, but over time you should have a short-term memory for failures and a long-term memory for success. Keep a vivid mental catalog of your greatest performances.

Get involved - Autonomy directly improves motivation, and perhaps the greatest contributor to autonomy is having input on decisions that affect you.

In both individual and team-sport settings, athletes should feel ownership of training rules, competition choices, and strategy decisions. Interestingly, on the professional level, many head coaches comment that their success depends entirely on their players’ belief in the “system” or playbook. The easiest way

to ensure this is to get them involved!

Praise others - If you can’t see positive or exciting things in the athletes and coaches around you, how can you do the same for yourself? Moreover, a sense of connectedness depends on everyone’s awareness of the contributions that others make.

Vary training - An imbalance between high competence and low task difficulty can result in boredom. So too can constant hammering at one task. A significant portion of training—just as much as is reserved for skill advancement—should be devoted to play for the sake of play, without rules or evaluation.

Put yourself first - Human beings are most productive at homeostasis since in that state they are not distracted by conflicting basal drives. Make sure to eat properly, stay hydrated, and get ample rest.

Find motivated peers - Both on and off the playing surface, spend your time with people who want to accomplish great things, aren’t afraid to talk about it, and get revved up by other people’s dreams. An effective support system is vital to motivation, especially during difficult times. Conversely, motivational

“black holes” are people who always criticize the coach, moan about bad calls, loaf in practices and workouts, and generally focus on obstacles, frustrations, and what can’t be achieved.

Think positively - What conversation goes on in the back of your head? It’s with you all day, but how much of it do you pay attention to? Actually, all of it, subconsciously. You’d better start paying conscious attention. Is it positive or negative? Is it about what you can do or what you can’t do? Is it hung up on difficulties or engaged in a search for solutions?

Remember your dream - Don’t make revisiting your dream a rare event. Spend time frequently reconnecting with the real reason why you perform—once again the heart, soul, and will of it all.

.jpg)

.jpg)